Summary: In this post I recap the paper “Out of the Tar Pit” that gives answers to a fundamental question in software development: is complexity inevitable or can it be avoided? What is complexity in the first place and what are possible remedies?

Does software have to be complex? Is it unavoidable that any growing software system gives rise to more complexity and every new feature or change makes it more error prone? Or is there hope (on the far horizon) that complexity can be avoided and we just haven’t figured out yet how?

It’s a fundamental question. In our daily lives as software developers we try to produce “quality” code that is clean, robust and reliable. This is often more art than science (or engineering) and depends on how well the problem we try to solve is understood and how thorough we test and refactor. But if complexity is inherent in software development all we can hope to do is to minimize the damage. That is not very satisfying and I’m wondering if we can’t do better than that.

In a series of blog posts I’d like to find some answers. Today I start with a paper that is considered 1 to be a classic: “Out of the Tar Pit” by Ben Moseley & Peter Marks 2

What is complexity and why is it a problem?

Complexity is the root cause of the vast majority of problems with software today.

If we we agree that complexity is the main culprit for our problems with current software the first question to answer is: what is complexity?

The authors define complexity indirectly as something that makes a system hard to understand. From this follows the opposite: simplicity makes a system easy to understand. However, “simplicity is hard” and as Rich Hickey would say that “simple is not easy” 3 that “easiness” of understanding may still require effort and experience.

How can we “understand” a system then? There are two ways:

- from the outside: testing

- from the inside: informal reasoning

With Testing we are treating a system as a black-box and observe its behaviour from the outside. Informal reasoning attempts to understand a system from the inside by examining its parts and inner workings.

Testing leads to the detection of more bugs, whereas informal reasoning leads to less errors being created. From that standpoint informal reasoning is more important of course. As a developer that is what I mean by “understanding” a system, that I can reason about its inner workings. Testing is limited and almost impossible to do without any reasoning about the system.

What causes complexity?

Now we come to the interesting part: where does complexity come from? What are the causes?

The number one enemy is this ugly little guy called state. The recent popularity of functional programming languages shows the desire to tame this beast. What is the problem with state regarding to understanding?

- The behaviour of a system in one state tells you nothing about the behaviour in another state. Testing tries to get away with this by always starting in a “clean state”. But that is not always possible and a system can get too easily into a “bad state”.

- Informal reasoning often resolves around a case-by-case simulation of the behaviour of a system. Each new state doubles (at least) the possible states to consider and with this exponential growth the mental approach reaches very soon its limits.

- State can contaminate and spread through a system. A part that has no state but a dependency to another stateful part becomes automatically affected by that state.

The second cause of complexity is control. Which is basically the order in which things happen. The problem with control is that in most cases we don’t want to be concerned with it but are enforced to do so due to the limits of the programming language. We have to over-specify a problem.

Other causes:

- Sheer code volume. The authors disagree that complexity has to rise in a non-linear way with the amount of code lines of a system. In other words: complexity is not necessarily inherent in software.

- Complexity breads complexity: see above regarding state, complex parts can contamine other parts. It is therefore important to contain complexity.

- Simplicity is hard. It requires effort to keep a system simple.

- The power of a programming language creates complexity. The more I can do with it, the more ways I have at my hands to create complexity.

Two types of complexity

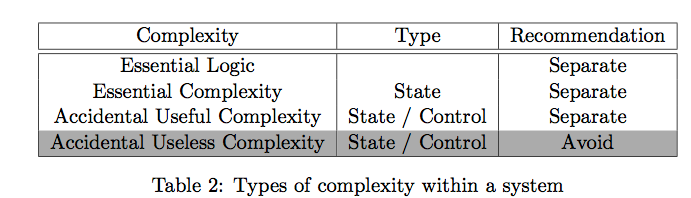

We know the causes of complexity and what it does to our understanding of a system. So what can we do about it? The authors define two types of complexity:

- Essential complexity, which is inherent in the problem itself (as seen by the user).

- Accidental complexity is all the rest and which would not appear in an ideal world.

The word “essential” is meant in the way of strictly essential to the users’ problem. If there is a possible way a development team can produce a correct system (in the eyes of the user) without the need of that type of complexity it is not essential.

How can we avoid complexity in the ideal world?

To determine what type of complexity can be avoided the authors first look at the best possible solution that could exist if we lived in an ideal world.

In this world, following things are true:

- We are not concerned with performance.

- When we translate the users’ informal requirements into formal requirements, the formalisation is done without adding any accidental aspects at all.

- After formalisation the only step left to do is to simply execute the formal requirements on our underlying infrastructure.

The last step is the very essence of declarative programming: we only specify what we require but not how it must be achieved. There is therefore no need for control in the ideal world.

State & data in the ideal world

State in the ideal world only depends on data that the user specifies in the informal requirements. The authors distinguish between following types:

- Data is either provided directly to the system (as input) or derived.

- Derived data is either immutable or mutable.

With this we get four types of data:

- Input data: data that is specified in the requirements is deemded essential. However, only if there is a requirement that it might be referred to in the future. If that is not the case, there is not need to store the data and the resulting state is accidental.

- Essential derived data that is immutable: that data can always be re-derived and is not essential.

- Essential derived data that is mutable: modifications to the data can be treated as applying a series of function calls on the existing essential state and is therefore also accidental.

- Accidental derived data: this state is derived but not in the requirements of the user and therefore not essential.

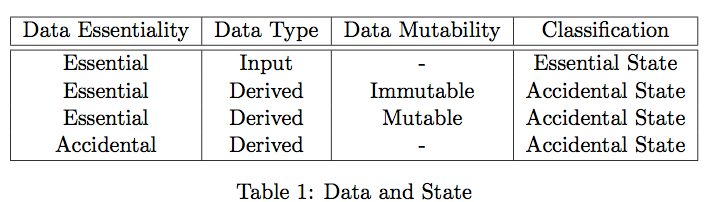

Summarized in following table:

Only input data that has to be stored is therefore essential. Control is considered entirely accidental as it can be completely omitted in the ideal world.

The real world

In the real world things are of course not as easy and some accidental state might be required:

- Performance: in some cases performance is an issue and requires accidental state (eg. cache). The recommendation to deal with it is to restrict ourselves to simply declare it and leave it to a completely separate infrastructure to deal with it

- Ease of expression: in some cases accidental state might the most natural way to express logic in a system.

The authors give us two recommendations to deal with complexity in the real world:

- Avoid accidental complexity where possible

- Separate out all complexity from the pure logic of the system

The main implication to keep in mind is that the system should still function correctly even if the “accidental but useful parts” are removed.

Designing a system

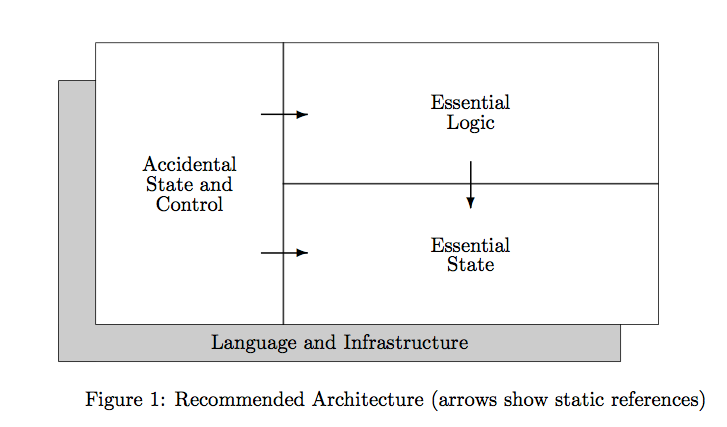

The authors finally recommend an architecture of a system that follows the guidelines:

The arrows show the dependencies of such a system:

- Essential state: is the foundation of the system and completely self-contained such that it makes no reference to any other part. Changes here may require changes in the rest but never the other way around.

- Essential logic: the “heart” of the system which is often called “business logic”. This part does depend on the the essential state but nothing else.

- Accidental state and control: the least important part of the system, changes here can never affect essential logic or state.

Key takeaways

Start with the ideal world and ask: what type of complexity is unavoidable? The answer is only the one that is required by the users’ requirements. Everything else should be considered accidental. That gives us an important distinction: complexity is either essential or accidental.

The main causes of complexity are state and control. State makes reasoning and testing exponentially more difficult. Control is completely accidental. Also, complexity spreads and contaminates so it is important to contain it.

In order to design a simple system we need first to avoid complexity and if that’s not possible separate complexity from the logic of the system.

So what is the final answer to the ultimate question: is complexity inevitable and inherent in software? The authors give hope that most complexity could be indeed avoided and systems could be much simpler and easier to understand and therefore more reliable and bug-free.

Note: if you want to see a real system that follows the recommendations have a look at the second part of the paper (which I haven’t included in my review) where the authors propose a solution called Functional Relational Programming.

Thanks for reading

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. If you have comments, questions or found a bug please let me know, either in the comments below or contact me directly.